In this month’s blog post we look at the first ever reprint of Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage, a book first published in 1967 that unpicks the structures of apartheid.

Read more about Photobooks in previous blogs:

- Laia Abril and Rafal Milach: Windows on the world of Misogyny

- Women and Photobooks: Unwriting History

- The Grid: Bringing Order, Comparison and Narrative to the Story

- Photobooks and the Archive

- Photobooks and the Unreliable Narrator

- Photobooks and the Immersive Landscape

There are many conflicting ideas about documentary photography and photojournalism. Susan Sontag (in On Photography) says that photography is essentially voyeuristic, that ‘The camera is a kind of passport that annihilates moral boundaries and social inhibitions, freeing the photographer from any responsibility toward the people photographed’.

In The Cruel Radiance, Susie Linfield presents an opposing view that challenges the idea that photographs of political violence exploit their subjects and pander to the voyeuristic tendencies of their viewers.

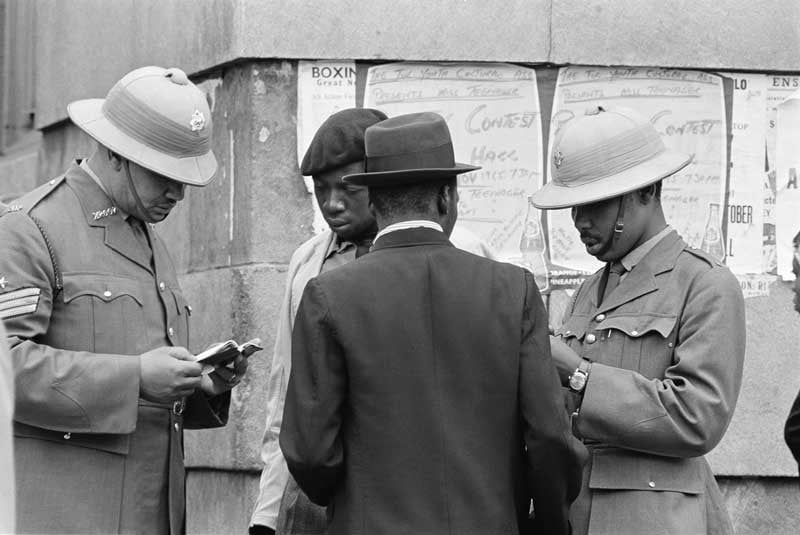

Police check passes for employers signature, Ernest Cole (ca. 1960s)

You can double back to Martha Rosler who famously said that, ‘Documentary, as we know it, carries (old) information about a group of powerless people to another group addressed as socially powerful.’

Judith Butler comes up with a different view. ‘For photographs to accuse and possibly invoke a moral response, they must shock,’ while Pete Brook (who ran the influential Prison Photography blog) says that. “I suspect images might have a very limited role to play in activism. My hope would be that (photographers) employ more caution when it comes to referring to either themselves or others as activists.”

Such is the nature of photographic criticism when it appears in a vacuum. How it applies to specific photographers is a different matter. Take Ernest Cole for example, the author of House of Bondage. First published in 1967, this was a hard, cold, stripped down analysis of apartheid.

In 13 chapters with titles including The Mines, The Cheap Servant, For Whites Only, Nightmare Rides, and Police and Passes, it laid out how the apartheid regime marginalised black South Africans in every way possible. It’s a book about the dehumanisation of a people, and how that dehumanisation manifests itself both in those who are oppressed and those who accept that oppression, and the apparent benefits it brings.

Busy train station platform, Ernest Cole (ca. 1960s)

That is evident in Cole’s image of a station platform during an early morning commute. On one side of the platform stand seven solitary white figures, all waiting to get in a whites-only carriage where there will be seats, there will be room, there will be air. On the other side stand black commuters, packed onto the platform. And if you want to see how full their train will be, you just have to turn a page and you will see Cole’s pictures of packed carriages taking exhausted commuters to and from their destinations.

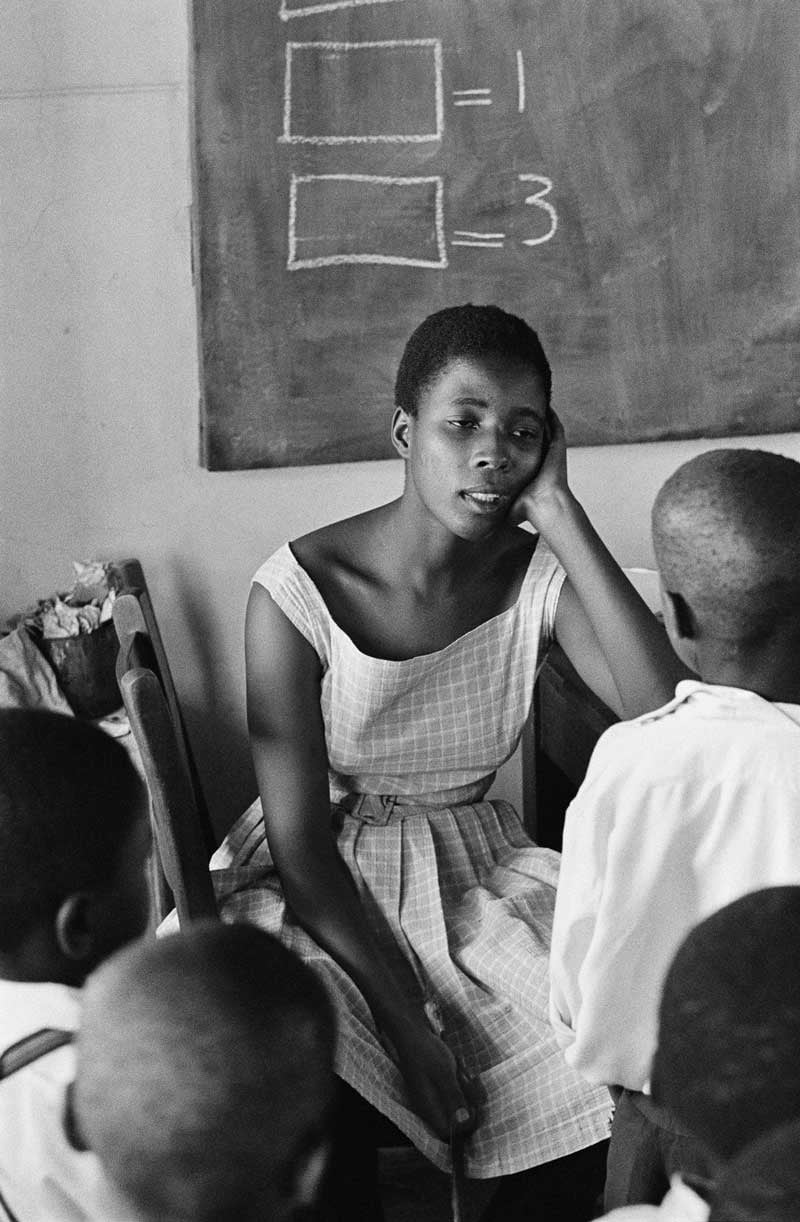

Enforced exhaustion through apartheid is the name of the game here. Overcrowding, run-down facilities, over-zealous and discriminatory bureaucracy, and the constant knowledge that you are living in an unjust society add anxiety to the mix and you can see all these elements combining in Cole’s images of hospitals, schools, housing, and policing.

Teacher toward end of her day in school in South Africa, Ernest Cole (ca. 1960s)

Life is a struggle in House of Bondage, and Cole (who wasn’t regarded as an activist at the time the pictures were made, who was less political than others) shows why it can’t be anything but a struggle. All the odds are stacked against the black South Africans he photographs, and he lays out how and why this is the case from start to finish both in his pictures and in the accompanying text.

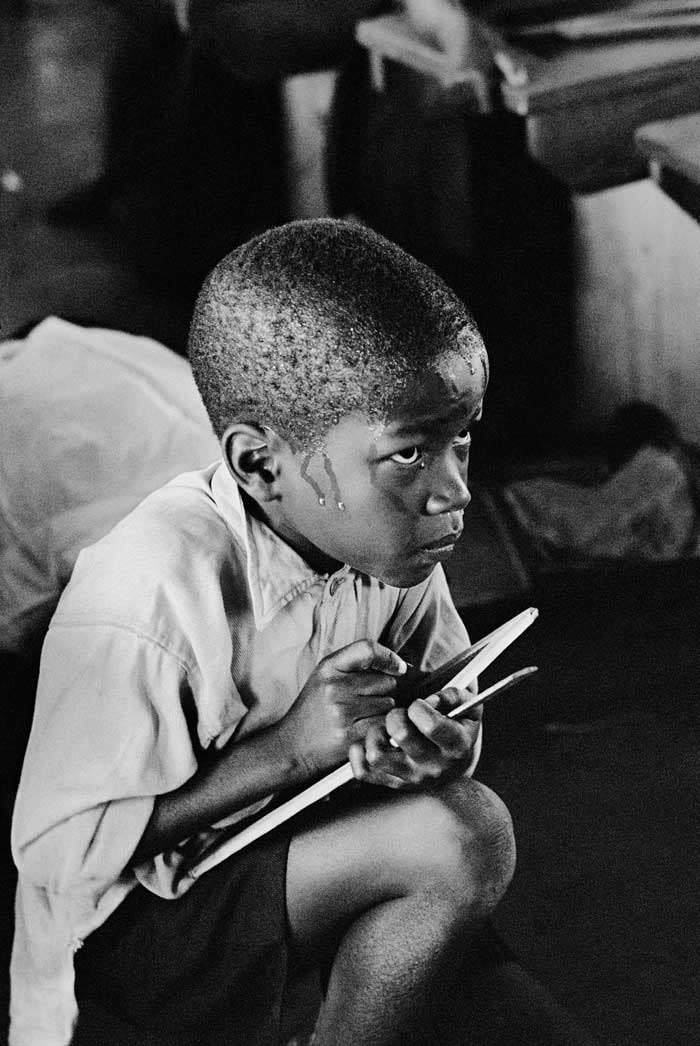

Earnest boy squats on haunches and strains to follow lesson in South Africa, Ernest Cole (ca. 1960s)

His image of the ‘earnest schoolboy’ squatting on his haunches as he strains to follow the lesson is an example. Sweat drips from his brow as you see him working to focus in a room with desks or chairs where there might be 100 pupils in a class. And it’s a class in a school in an education system determined by whites. In 1953, Hendrik Verwoerd, the then Minister of Native Affairs and a future prime-minister, proclaimed, “When I have control of native education, I will reform it so that natives will be taught from childhood to realize that equality with Europeans is not for them.”

House of Bondage reveals the process by which white supremacism tries to enforce this idea. It is book that does reveal the lives of the less powerful, that is made by a photographer who was not an ostensible activist, who didn’t bear responsibility for the people photographed. How you weigh up all those initial ideas in the light of this work is a conundrum that perhaps has no solution. Ideas are not a polarised zero-sum game, even when they are presented as such. .

In Leopold’s Legacy, Oliver Leu’s book on post-colonial remnants in Belgium, Bambi Ceuppens writes, ‘What moves us are images, memories, music, objects, songs, sounds and statements that individualise victims and in doing so, allow us to identify with them.’

That idea forms the basis of the final chapter in House of Bondage. Titled Black Ingenuity, it shows black South Africans having their own agency as they engage in the arts of singing, dancing, painting, performing. This is the only visual addition to this version of House of Bondage, a reminder that no matter what the oppression, the human spirit can and will continue to find a means of expressing itself.

Woman sitting on bench, ca. 1960s (Ernest Cole)

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer and teaches on the MA Photography programme at Falmouth University.

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer and teaches on the MA Photography programme at Falmouth University.

.webp)