In this month’s blog post we look at photography and fishing through Tessa Bunney’s Going to the Sand, a detailed examination of traditional fishing around Morecambe Bay, and Giovanni Bienvenuto’s Solo il mare sà, an ongoing project that looks at life aboard a small trawler fishing off the coast of Sicily.

Going to the Sand, Tessa Bunney

Image 1: Far-reaching stretches of wet sand at Morecambe Bay. © Tessa Bunney

Going to the Sand is what the fishermen and fisherwomen of Morecambe Bay have done for years. Instead of getting into boats and sailing out to sea, they trudge out into the far-reaching stretches of sand to fish for shrimps and plaice, to rake for cockles, or to put nets out for salmon and trout.

Image 2: Thick fog on the sand on a cool early morning © Tessa Bunney

Bunney worked for years following the fishermen as they sought their catch. It’s brutally hard work, compounded by an Irish Sea climate that can change from bright sunshine to tipping rain in a matter of minutes.

On the sands, that can equate to overexposure and death, as can the rising tides that swirl into the deceptive calm of the sands, the channels of water that thread through the cockle beds, and the disorientation that can result from the wide-open spaces when you are miles from shore.

Image 3: A fisherman in yellow catches fish in the bay © Tessa Bunney

Her images detail the different forms of fishing, the lives of the people who work on the sands, the process of harvesting and transporting their catch, and the environment in which they practice their work.

And it’s hard work, the labour apparent on the faces of those she photographs. They rake, they bend, they load, they carry the cockles that they rake from the sands. The cockles being the most lucrative of all the catches in the bay, but also the ones that are the most threatened by pollution and overfishing.

Image 4: Two fishermen and their dog working on the sand on a clear day © Tessa Bunney

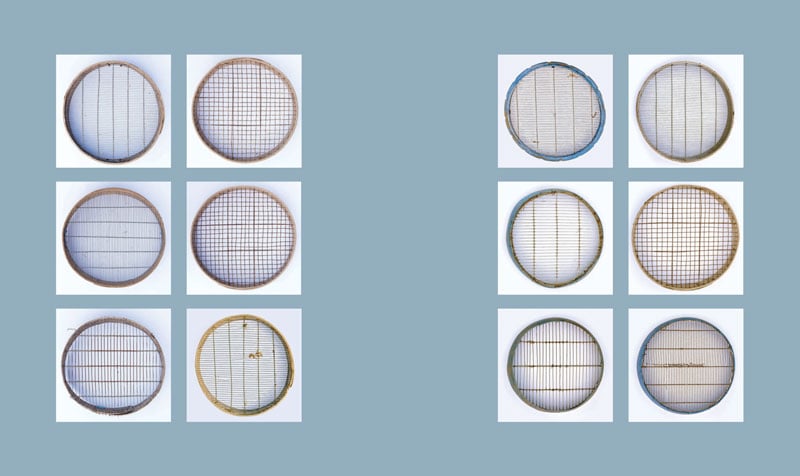

There are grids of the sieves they use to catch prawns (small brown Morecambe Bay prawns, cooked with butter to make potted shrimp are the traditional catch in the area), there are the different kinds of nets used to catch ‘fluke’ and plaice, as well as the nets that are used to catch salmon as they come in with the rising tide and then turn back as they hit the fresh water of the estuary.

Image 5: Grids of the sieves and nets used to catch different types of fish © Tessa Bunney

At the heart of the book is the idea (as told in a conversation between myself and Bunney) that harvesting the land and sea, living off that land is something that resonates with the way we used to live.

“Fishing is in people’s blood,” says Bunney, “it’s part of them and there’s something to be admired in that. It connects back to that being in the landscape, to connecting with the hunter-gatherer side that we all have in us somewhere.”

“That’s why fishing in Morecambe Bay will survive, even if only on a part-time basis. With industrial scale fishing around the globe depleting offshore fishing stocks, there are fewer and fewer small inshore fisherman. But it is the industrial scale fishing that is the anomaly. That has been with us only for a few decades. Small scale fishing has been with us since people walked the earth. And when industrial fishing has depleted all the stocks in the ocean, there will still be people fishing on Morecambe Bay.”

Image 6: Fish caught in nets © Tessa Bunney

That idea of a small fishing industry set against the industrialised might of fish-processing factories on boats and the immense scale of the international fishing industry is something that the smaller fishing industries understand around the world.

Solo il mara sà, Bienvenuto

It is an idea that is at the heart of Giovanni Bienvenuto’s project, Solo il mare sà (Only the sea knows). In this project, Bienvenuto followed the fishing communities of Trapani and Portopalo in Sicily as they sailed out into the Mediterranean in search of swordfish, sardines, anchovies, and mackerel.

Image 7: Seagulls fly across a dark sky © Giovanni Bienvenuto

Sicilian trawlers form a huge part of the Italian fishing industry, but it’s small-scale fishing for the most part, in stark contrast to factory boats, with large scale processing and refrigeration capabilities.

The coastal tuna fishing that was once such a staple of Sicilian fishing (Salgado, among many others, photographed it) is highly limited due to over-fishing, so now the people Bienvenuto travelled with go out into the straits between Sicily and Tunisia and Libya.

Image 8: Fishermen in Sicily sort through their catch © Giovanni Bienvenuto

It’s tough work, one where the rigours of the sea, the physicality of the labour, come up with the harsh environmental and economic realities of everyday life. This is work with an irregular flow of income. The occasional bumper harvest is offset by small catches, and poor sales at market. The dilemmas of this kind of fishing is laid out in the beautiful Maltese film, Luzzu, a film where the changing dynamics of fishing are set out against the realities of domestic, and in particular, family life.

Image 9: Fishermen working in dark and rainy conditions © Giovanni Bienvenuto

Bienvenuto photographs both the hardness of the labour, and the way the sea has imprinted itself on the faces and bodies of the trawlermen he followed (and befriended) as he photographed, but also hangs out with them in their down time onshore. It’s a time when many of the fishermen return to their families. Others however, miss the sea, their homes becoming replicas of the cramped confines they inhabit, their free time spent on wharfs, as close to the boats as it is possible to be.

Bienvenuto photographs these people, he identifies with their struggle, positioning it as the struggle of the little man, the community, and the ancient industry of a group living with the Mediterranean. It’s work as resistance, resistance to factory ships, globalisation, and homogenisation.

Where Bunney is detailed in her visual description of Going to the Sand, answering the questions that are on the tip of one’s tongue, Bienvenuto photographs with a cinematic passion, transforming simple fishermen into symbols of a global struggle.

Their photography is also different. Bunney works with the flat surfaces of the bay, the level horizon, the weather coming in from the Irish Sea, while Bienvenuto works with the shifting surfaces of the trawler boat, often at night. Here, there is no horizon, you do not see the weather coming.

Both however, have the same message, one of the essential connection between people and the sea, a struggle that is elemental, laborious, and fundamental to life.

Image 10 and Image 11: Sicilian fishermen in their homes © Giovanni Bienvenuto

.webp)

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer and teaches on the

Colin Pantall is a photographer, writer and lecturer and teaches on the